Last Christmas in Nova Scotia, America and their Hopes of a Better and Brighter New Year in Sierra Leone, Africa.

Draft Literature and Oral Research by Adrian Q. Labor ([email protected]) Jan 15rd, 2022 Edition.Recreating our story across generations: Our story: recounting our ancestors’ courageous stories from a hopeful spring in New York in 1783 to a thanksgiving under the Cotton Tree in Freetown in March 1792, 230 years ago. In telling this story, if I start with the opening phrase of “Il aw? Wan de ya”, siblings, aunties,

uncles and grandparents will know that this is a “nansi stori” filled with history, folktale and wisdom expressed in Krio parables. They also know it is best told orally, with everyone gathered in one place, and with the sounds and intonations to enhance the story. If, on the other hand, I start by stating this is a history lesson, the children and grandchildren will hope that I would make it into a short text and make it available online or as a podcast so they can listen on their phones while they do other things. Regardless of how I tell the story, the historic accounts I will share are steeped in 18th century language and contexts far removed from today’s lifestyles and realities so bear with me. “Fambul dem” with the help of a focus group of family members across the generations, I am recounting the pivotal

episodes of our family story that happened over two centuries for the benefit of all.

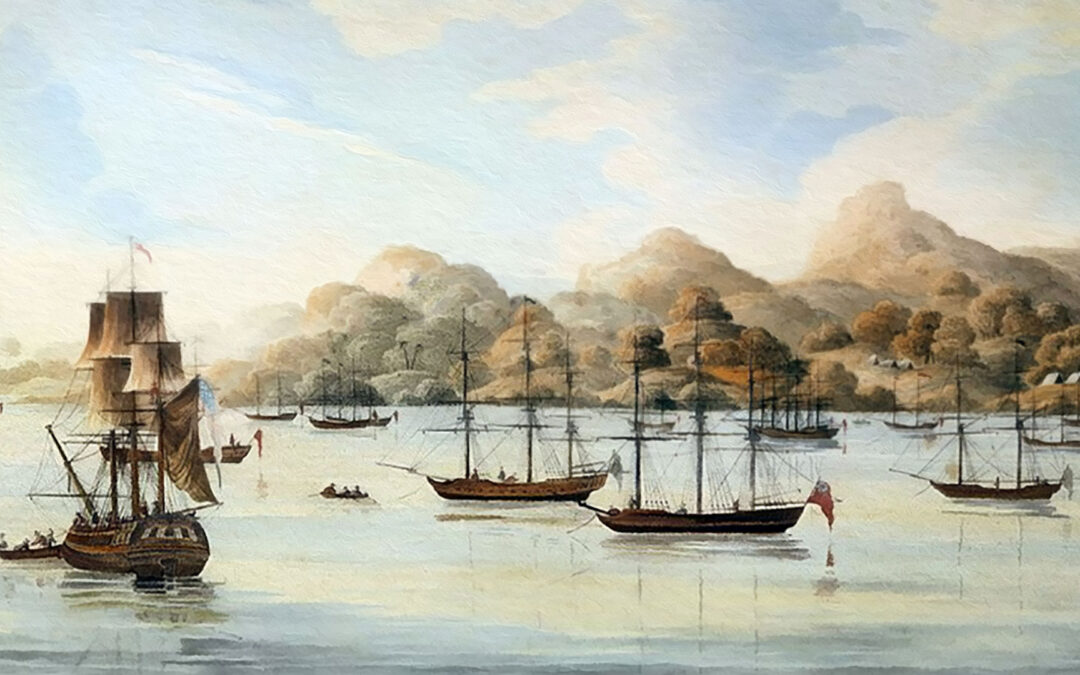

Thomas Peters and David Edmon, 23 December 1791

Halefax December the 23 1791

The humble petion of the Black pepel lying in mr wisdoms Store Called the anoplus Compnay humbely Bag that if it is Consent to your honer as it is the larst Christmas day that we ever shall see in the amaraca that it may please your honer to grant us one days allowance of the frish Beef for a Christmas diner that if it is agreabel to you and the rest of the Gentlemon to whom it may Concern

Thomas Petus

David Edmon